A dangerous neighborhood prompts a pre-school program to build something really big.

It’s hard to learn in Austin, Chicago’s largest neighborhood. Austin is thick with barriers—poverty, domestic abuse, street violence. In fact, it’s so hard to attend classes and stay on track that in 2021, only 58 percent of seniors graduated Austin’s largest public high school. Also in 2021: More than 220 people were shot in the first eight months of the year. Austin is what people sometimes call “a tough neighborhood.”

It’s also Donnita Travis’s kind of neighborhood. After a career in advertising, Travis founded her first after-school program in the infamous Cabrini-Green housing project, serving 16 children with tutoring and activities. Today, By The Hand Club serves 1,600 children in five locations.

But it’s Austin where By The Hand’s team came up with the strategy of encirclement—the idea of keeping kids engaged, learning, and in the same building from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. every school day. As undoable as it sounded, the strategy made sense: The kids would be safe, there wouldn’t be complications around transport, they’d be in familiar territory with familiar faces and rules. They would experience a nearly seamless day of education, recreation, and care. And the barriers that popped up outside the building? They’d be addressed with case work and coaching. “Our job is to identify any barrier that could keep that child from learning and remove it,” says Travis.

The first step? Build a 50,000-square-foot building and make a school.

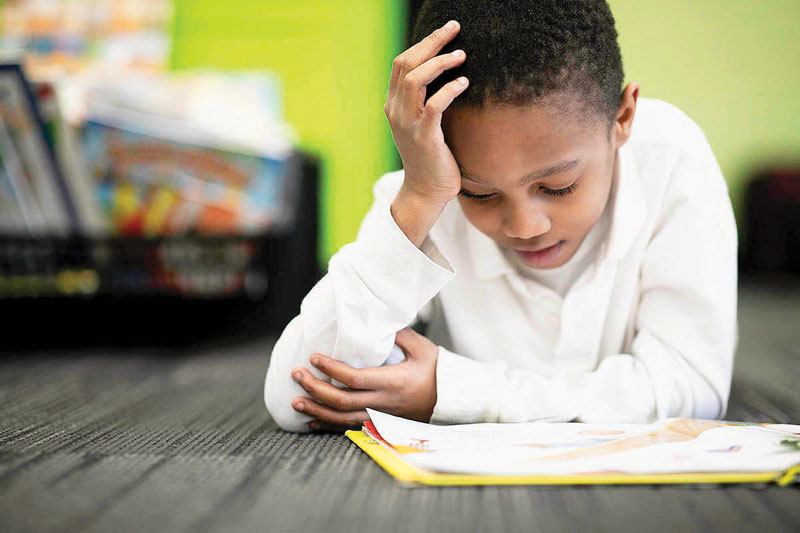

In the fall of 2015, Moving Everest Charter School opened 190 kindergartners and first graders who were, on average, already behind their peers by 1.5 years (see sidebar). Alongside the school—literally down the hall—was By The Hand Club For Kids.

Among the first graders was Chitola, who lives in the neighborhood with her little sister, three other children, and her adoptive mother, Miss Alma. Chitola was quiet, anxious, and, like most of her peers, already behind in school. The barriers were, Travis says, mostly social and emotional. Today, Chitola is a confident eighth grader, reading at the twelfth-grade level. Her peers have thrived, too: At the conclusion of the 2018–19 school year, 79 percent of students were reading at or above grade level, up from 40 percent.

Powering that success is a range of tactics, including an emphasis on literacy, parent involvement, and a rites of passage curriculum designed specifically for Black youth. But perhaps the most significant element is academic integration. After-school teams, which consist of a team leader, assistant leader, and academic specialist, are matched with classrooms; they know the kids and the coursework. They also know the teachers. “They rub shoulders with them,” Travis says. “I don’t know what this world is going to look if we have to live without interaction. A lot takes place when people are in the same place.”

And when an ugly barrier pops up, “We spring into action.” Two common barriers—lack of dental and eye care—are addressed regularly. By The Hand also does home visits. “We’re a liaison between parents and the school,” Travis says.

Meanwhile, Miss Alma, Chitola’s mom, has become the By The Hand greeter, the first line of security. “She knows all the kids, all the parents,” says Travis. “It’s a hard job. There’s a lot of de-escalating. And she does it well.”

Encirclement—safe, purposeful, strategic. It takes an idea, a building—and a community.